I’ve always enjoyed financial planning. I think a lot of it comes from certain similarities to Physics (which was my undergrad major): you create simplified models with certain assumptions (frequently used as parameters), and then adjust those parameters to see how the behavior or output might change. When trying to figure out how much money you’d hypothetically have at retirement, you have to know

- How much money you start with

- How much you think you’ll add each year (the younger you are, the more of a guess this is for later in life)

- The average rate of return you expect on the investment mix (above and beyond inflation)

- Your current age

- When you plan to retire

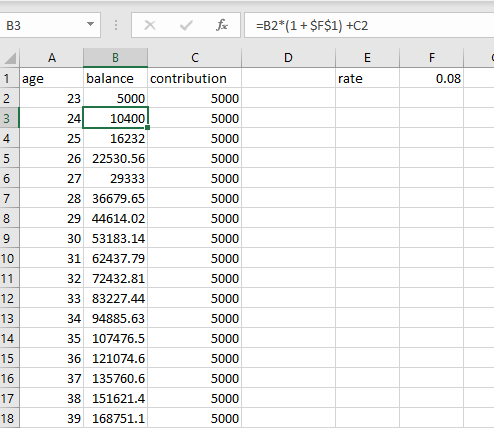

If you can put all of those into a spreadsheet, it is reasonably straightforward to add formulas that will show your expected balance for any given year (basically: (balance last year*( 1+ rate/100) + amount added current year) ) – then fill down, using the cell above as the balance last year. This of course ignores inflation, but I like the simplification of doing everything in current dollars and just building the inflation expectation into the rate of return.

As a simple example, assume you are 22 – fresh out of college – and start a job at 50k, of which you save 10%, which you invest in an asset mix heavily weighted in equities, so you can assume a rate of return after inflation of 8% (that may be a bit high, but we’ll use it for this example).

So, at the end of year 1, you’ll have something like $5000 (we’ll ignore the gains during the year on newly invested amounts as they are relatively small, although compounded over time could add up to a lot). At the end of year 2 you’ll have $5000*1.08 + $5000 or $10400. At the end of year 3 you’ll have 10400*1.08 + $5000 or $16232. And so on, and so forth. If you put this model into a spreadsheet, you wind up with $1,932,528 at retirement age (67)… not a bad haul.

But wait, there’s more! In addition to adjusting the avg rate of return up or down to gauge the impact, you can also play around with the contribution column. Ideally/hopefully your income will go up over time as you gain experience and prove your stellar-ness to your employer(s). So (for example) you could change that column to show your contribution going up 2% a year (faster than inflation). In that case by the time you retire you’re making almost $120k, and your retirement savings jumps to $2,411,606 at age 67.

Obviously reality is a lot messier – a good example is “average rate of return.” Some years the stock market may return 30%, other years -20%, and other times it may be pretty flat for a long time. So, the “average rate of return” is really only useful over long periods, and even then what happens in the years closest to retirement may have an enormous impact on your asset balance when you retire. However, trying to model this is very complicated, and turns retirement planning into an exercise in probabilities, so I personally stick with the simple model. Guessing future contributions is difficult also… if you stay in the same job a long time your income may actually stay flat, or barely beat inflation, but if you switch jobs or get promoted you may see big jumps. You may also see big drops if you change careers mid-life, get laid off, etc.

You can’t plan for every possibility – just have to make some reasonable (and hopefully conservative) assumptions and periodically check your progress against your projections.

Disclaimer: don’t take financial advice from a programmer.

The biggest and hardest parameter for me that is required for any of these calculations to work is: How long do you think you will live? I do my own spreadsheet as well because I find most tools lacking. Trying to account for income in retirement, like social security or whatever I might make from some other source, I had to handle as just reductions to the amount of savings I would need to draw down in a given year. Playing with the parameters, making them unreasonable (in my case) whereby the annual return on savings is greater than what you intend to spend in a year gives a great eye opening lesson as well, with regard to why wealth in large quantities spirals upward, as you see the balance actually go up in time versus down. I have told my kids not to expect that outcome in my case. Good reminder though, now that I am actually retired I should take a look at mine.

My father-in-law is a retired actuary so I can see if he knows when you’ll die.

But yeah, that is always the rub. If you feel like you are going to outlive your savings I have a few lifestyle choice recommendations that will fix that right up, but there is also the other possibility… that you saved too much. The worst case there isn’t too bad – your children or grandchildren could be mini-trust fund babies, but if you lived your whole life feeling like you couldn’t do what you wanted because you had to save for retirement, that isn’t good either.

Comments are closed.